[译]终结一个进程和它的所有后代

终结一个类UNIX系统的进程可能比预期要复杂。上周我正在调试一个信号量停止工作导致的奇怪问题。更具体地说,涉及终结作业中正在运行的进程的问题。以下是我学到的内容的亮点:

- 类 UNIX 操作系统有很复杂的进程关系。父子进程、进程组、会话和会话负责人。但是,Linux 和 macOSX 等操作系统的细节并不统一。符合 POSIX 标准的操作系统支持向具有负 PID 编号的进程组发送信号。

- 在会话中向所有进程发送信号对于系统调用来说并不简单。

- 使用 exec 启动的子进程可以继承父进程的信号量信息。

杀死父进程不会杀死子进程

每个进程都有一个父进程,我们可以通过 pstree 或 ps 程序观察到这一点。

# start two dummy processes

$ sleep 100 &

$ sleep 101 &

$ pstree -p

init(1)-+

|-bash(29051)-+-pstree(29251)

|-sleep(28919)

`-sleep(28964)

$ ps j -A

PPID PID PGID SID TTY TPGID STAT UID TIME COMMAND

0 1 1 1 ? -1 Ss 0 0:03 /sbin/init

29051 1470 1470 29051 pts/2 2386 SN 1000 0:00 sleep 100

29051 1538 1538 29051 pts/2 2386 SN 1000 0:00 sleep 101

29051 2386 2386 29051 pts/2 2386 R+ 1000 0:00 ps j -A

1 29051 29051 29051 pts/2 2386 Ss 1000 0:00 -bash

ps 命令显示 PID (进程的 ID)和 PPID (进程的父 ID)。

关于这段关系,我有一个非常错误的假设。 我认为如果我杀死一个进程的父进程,它也会杀死该进程的子进程。 然而,这是不正确的。 相反,子进程变成孤儿,init 进程重新生成它们。

让我们看看通过终止 bash 进程(sleep 命令的当前父进程)来重新设定子进程的操作,并观察其中的变化。

$ kill 29051 # killing the bash process

$ pstree -A

init(1)-+

|-sleep(28919)

`-sleep(28965)

这种重新抚养孩子的行为对我来说很奇怪。 例如,当我通过 SSH 连接到一个服务器,启动一个进程,然后退出,启动的进程就会被终止。 我错误地认为这是 Linux 上的默认行为。 结束 SSH 会话时进程的终止与进程组、会话领导者和控制终端有关。

什么是进程组和会话管理?

让我们再次观察上一个例子中 ps j 的输出。

$ ps j -A

PPID PID PGID SID TTY TPGID STAT UID TIME COMMAND

0 1 1 1 ? -1 Ss 0 0:03 /sbin/init

29051 1470 1470 29051 pts/2 2386 SN 1000 0:00 sleep 100

29051 1538 1538 29051 pts/2 2386 SN 1000 0:00 sleep 101

29051 2386 2386 29051 pts/2 2386 R+ 1000 0:00 ps j -A

1 29051 29051 29051 pts/2 2386 Ss 1000 0:00 -bash

除了由 PPID 和 PID 表示的父子关系之外,我们还有两个其他关系:

- 由 PGID 表示的进程组

- 由 SID 代表的会话

进程组可以在支持作业控制的 shell 中观察到,比如 bash 和 zsh,它们为每个命令管道创建进程组。 进程组是一个或多个进程的集合(通常与同一作业相关联) ,它们可以接收来自同一终端的信号。 每个进程组都有一个惟一的进程组 ID。

# start a process group that consists of tail and grep

$ tail -f /var/log/syslog | grep "CRON" &

$ ps j

PPID PID PGID SID TTY TPGID STAT UID TIME COMMAND

29051 19701 19701 29051 pts/2 19784 SN 1000 0:00 tail -f /var/log/syslog

29051 19702 19701 29051 pts/2 19784 SN 1000 0:00 grep CRON

29051 19784 19784 29051 pts/2 19784 R+ 1000 0:00 ps j

29050 29051 29051 29051 pts/2 19784 Ss 1000 0:00 -bash

注意,tail 和 grep 的 PGID 在前面的代码片段中是相同的。

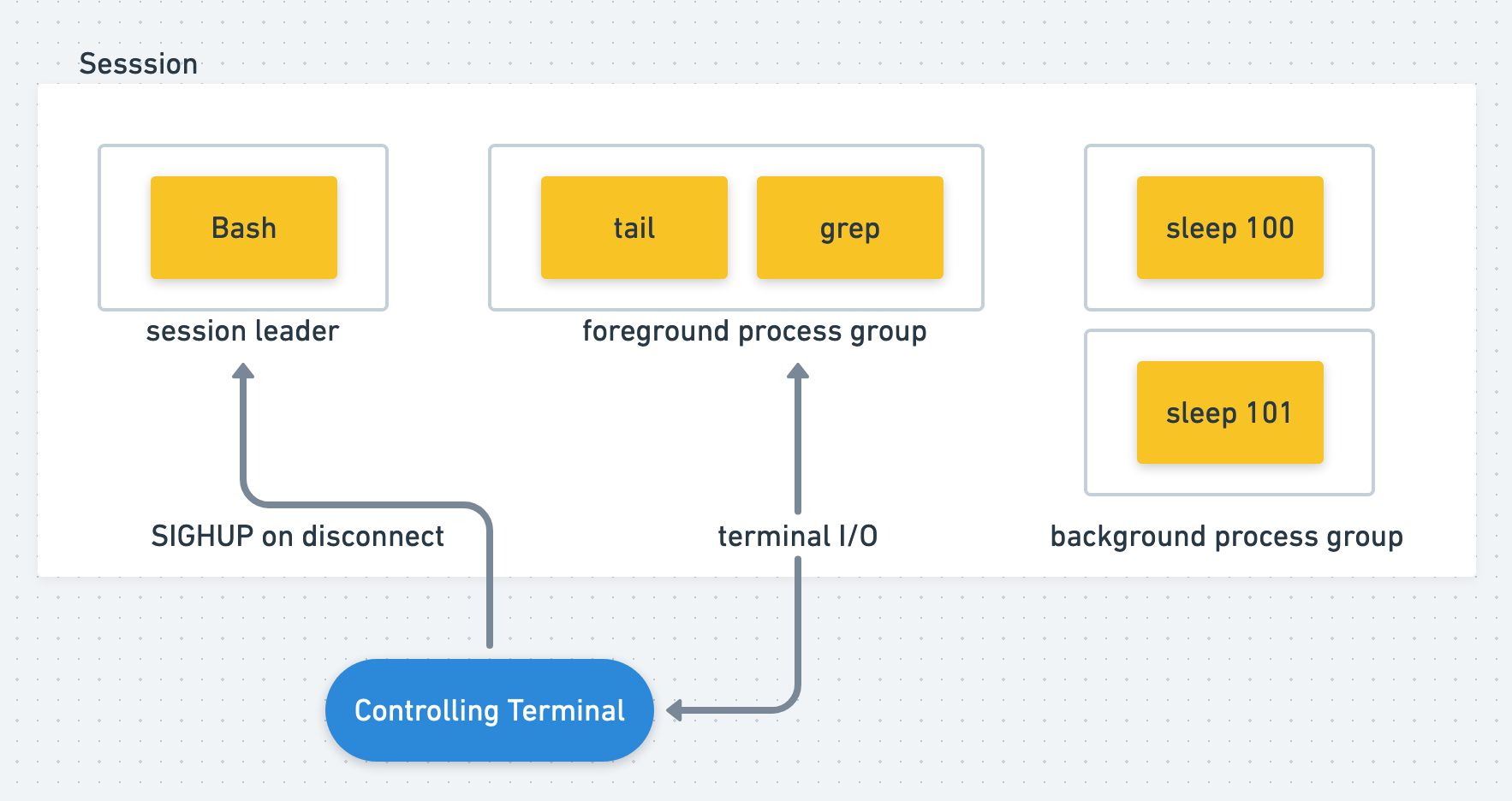

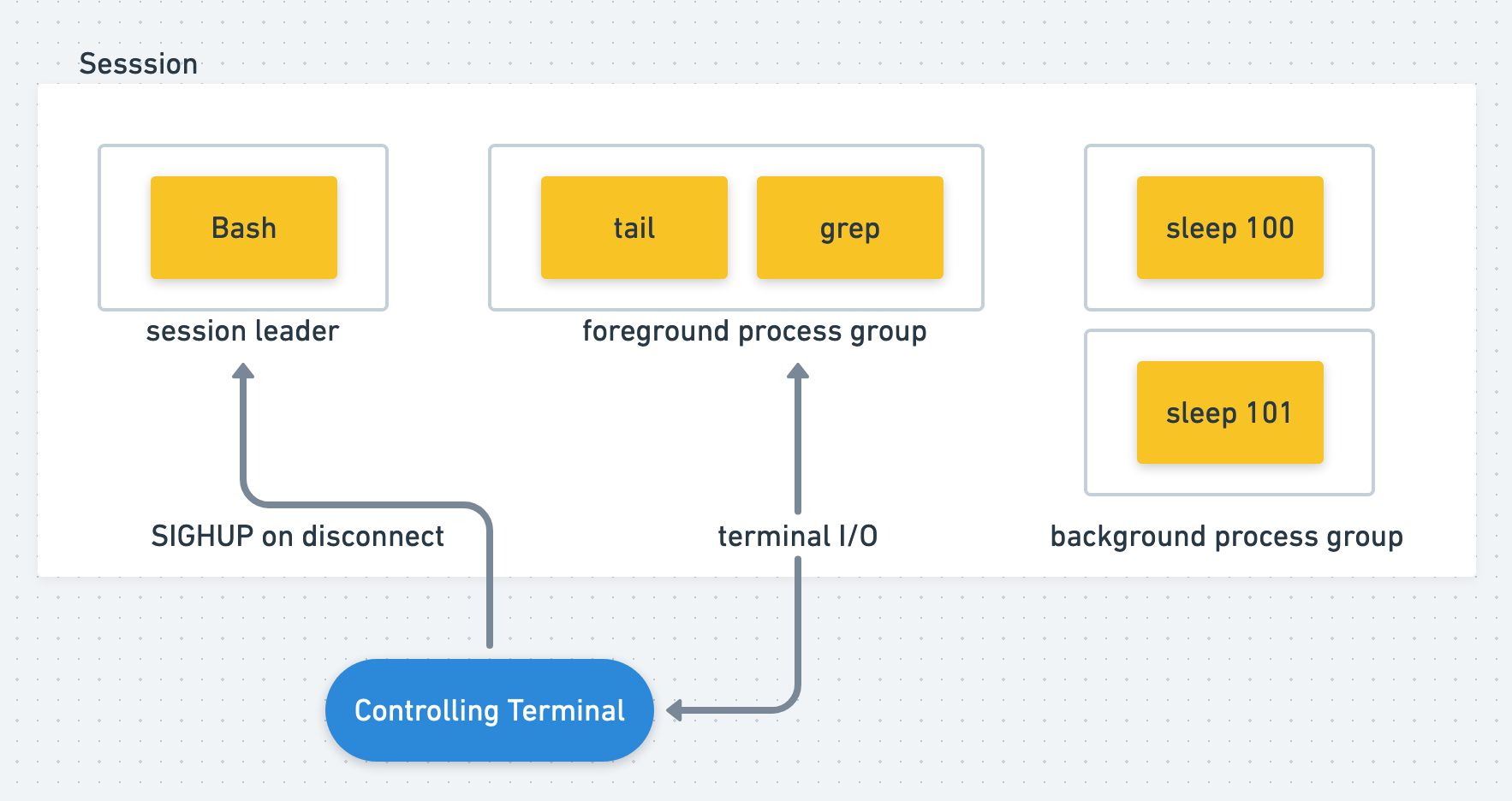

会话是过程组的集合,通常与一个控制终端和一个会话领导者过程相关联。 如果会话具有控制终端,则它具有单个前台进程组,会话中的所有其他进程组都是后台进程组。

会话在 Unix 实现中并不一致

并非所有的 bash 进程都是会话,但是当您 SSH 到远程服务器时,通常会获得一个会话。 当 bash 作为会话领导者运行时,它会将 SIGHUP 信号传播到其子进程。 SIGHUP 传播给子进程是我长期以来一直相信子进程与父进程同死的主要原因。

然而,您需要记住,这在所有的 Unix 实现中都是不正确的。 单一UNIX规范只谈论“会话领导者” ; 没有类似于进程 ID 或进程组 ID 的“会话 ID”。 会话领导者是一个具有唯一进程 ID 的单个进程,因此我们可以讨论一个会话 ID,它是会话领导者的进程 ID。

System V release 4 引入了会话 id。

实际上,这意味着在 Linux 的 ps 输出中会得到会话 ID,但在 BSD 及其类似 MacOS 的变体上,会话 ID 并不存在或总是为零。

终止流程组或会话中的所有进程

我们可以使用 PGID 通过 kill 工具向整个组发送信号:

$ kill -SIGTERM -- -19701

我们用一个负数——19701向组织发送一个信号。 如果 kill 接收到一个正数,它将使用该 ID 终止进程。 如果我们传递一个负数,它会用该 PGID 终止进程组。

在一个会话中终止所有进程是完全不同的。 正如上一节所解释的,有些系统没有会话 ID 的概念。 即使是那些拥有会话 id 的,比如 Linux,也没有一个系统调用来杀死会话中的所有进程。 您需要遍历 / proc 树、收集 sid 并终止进程。

Pgrep 通过会话 ID 实现了遍历、收集和进程杀死的算法。 使用下面的代码片段:

$ pkill -s <SID>

处理后代的 Nohup 繁殖

被忽略的信号,比如被 nohup 忽略的信号,会传播到进程的所有子代。 这种传播是上周我的 bug 搜索练习中的最后一个瓶颈。

在我的程序(一个运行 bash 命令的代理程序)中,我验证了我已经建立了一个具有控制终端的 bash 会话。 它是在 bash 会话中启动的进程的会话领导者。 我的流程树是这样的:

agent -+

+- bash (session leader) -+

| - process1

| - process2

我假设当我用 SIGHUP 关闭 bash 会话时,它也会关闭孩子。 对 agent 进程的集成测试也验证了这一点。

然而,我错过的是 agent 进程是以 nohup 开头的。 当您使用 exec 启动子流程时,就像我们在代理中启动 bash 流程一样,它从其父类继承信号状态。

最后一个让我大吃一惊。

Killing a process and all of its descendants

@igor_sarcevic · August 2, 2019

Killing processes in a Unix-like system can be trickier than expected. Last week I was debugging an odd issue related to job stopping on Semaphore. More specifically, an issue related to the killing of a running process in a job. Here are the highlights of what I learned:

- Unix-like operating systems have sophisticated process relationships. Parent-child, process groups, sessions, and session leaders. However, the details are not uniform across operating systems like Linux and macOS. POSIX compliant operating systems support sending signals to process groups with a negative PID number.

- Sending signals to all processes in a session is not trivial with syscalls.

- Child processes started with exec inherit their parent signal configuration. If the parent process is ignoring the SIGHUP signal, for example, this configuration is propagated to the children.

- The answer to the “What happens with orphaned process groups” question is not trivial.

Killing a parent doesn’t kill the child processes

Every process has a parent. We can observe this with pstree or the ps utility.

# start two dummy processes

$ sleep 100 &

$ sleep 101 &

$ pstree -p

init(1)-+

|-bash(29051)-+-pstree(29251)

|-sleep(28919)

`-sleep(28964)

$ ps j -A

PPID PID PGID SID TTY TPGID STAT UID TIME COMMAND

0 1 1 1 ? -1 Ss 0 0:03 /sbin/init

29051 1470 1470 29051 pts/2 2386 SN 1000 0:00 sleep 100

29051 1538 1538 29051 pts/2 2386 SN 1000 0:00 sleep 101

29051 2386 2386 29051 pts/2 2386 R+ 1000 0:00 ps j -A

1 29051 29051 29051 pts/2 2386 Ss 1000 0:00 -bash

The ps command displays the PID (id of the process), and the PPID (parent ID of the process).

I held a very incorrect assumption about this relationship. I thought that if I kill the parent of a process, it kills the children of that process too. However, this is incorrect. Instead, child processes become orphaned, and the init process re-parents them.

Let’s see the re-parenting in action by killing the bash process — the current parent of the sleep commands — and observe the changes.

$ kill 29051 # killing the bash process

$ pstree -A

init(1)-+

|-sleep(28919)

`-sleep(28965)

The re-parenting behavior was odd to me. For example, when I SSH into a server, start a process, and exit, the started process is killed. I wrongly assumed this is the default behavior on Linux. It turns that killing of processes when I leave an SSH session is related to process groups, session leaders, and controlling terminals.

What are process groups and session leaders?

Let’s observe the output of ps j from the previous example again.

$ ps j -A

PPID PID PGID SID TTY TPGID STAT UID TIME COMMAND

0 1 1 1 ? -1 Ss 0 0:03 /sbin/init

29051 1470 1470 29051 pts/2 2386 SN 1000 0:00 sleep 100

29051 1538 1538 29051 pts/2 2386 SN 1000 0:00 sleep 101

29051 2386 2386 29051 pts/2 2386 R+ 1000 0:00 ps j -A

1 29051 29051 29051 pts/2 2386 Ss 1000 0:00 -bash

Apart from the parent-child relationship expressed by PPID and PID, we have two other relationships:

- Process groups represented by PGID

- Sessions represented by SID

Process groups are observable in shells that support job control, like bash and zsh, that are creating a process group for every pipeline of commands. A process group is a collection of one or more processes (usually associated with the same job) that can receive signals from the same terminal. Each process group has a unique process group ID.

# start a process group that consists of tail and grep

$ tail -f /var/log/syslog | grep "CRON" &

$ ps j

PPID PID PGID SID TTY TPGID STAT UID TIME COMMAND

29051 19701 19701 29051 pts/2 19784 SN 1000 0:00 tail -f /var/log/syslog

29051 19702 19701 29051 pts/2 19784 SN 1000 0:00 grep CRON

29051 19784 19784 29051 pts/2 19784 R+ 1000 0:00 ps j

29050 29051 29051 29051 pts/2 19784 Ss 1000 0:00 -bash

Notice that the PGID of tail and grep is the same in the previous snippet.

A session is a collection of process groups, usually associated with one controlling terminals and a session leader process. If a session has a controlling terminal, it has a single foreground process group, and all other process groups in the session are background process groups.

Sessions are not consistent across Unix implementations

Not all bash processes are sessions, but when you SSH into a remote server, you usually get a session. When bash runs as a session leader, it propagates the SIGHUP signal to its children. SIGHUP propagation to children was the core reason for my long-held belief that children are dying along with the parents.

Sessions are not consistent across Unix implementations In the previous examples, you can notice the occurrence of SID, the session ID of the process. It is the ID shared by all processes in a session.

However, you need to keep in mind that this is not true across all Unix implementations. The Single UNIX Specification talks only about a “session leader”; there is no “session ID” similar to a process ID or a process group ID. A session leader is a single process that has a unique process ID, so we could talk about a session ID that is the process ID of the session leader.

System V Release 4 introduced Session IDs.

In practice, this means that you get session ID in the ps output on Linux, but on BSD and its variants like MacOS, the session ID isn’t present or always zero.

Killing all processes in a process group or session We can use that PGID to send a signal to the whole group with the kill utility:

$ kill -SIGTERM -- -19701

We used a negative number -19701 to send a signal to the group. If kill receives a positive number, it kills the process with that ID. If we pass a negative number, it kills the process group with that PGID.

The negative number comes from the system call definition directly.

Killing all processes in a session is quite different. As explained in the previous section, some systems don’t have a notion of a session ID. Even the ones that have session IDs, like Linux, don’t have a system call to kill all processes in a session. You need to walk the /proc tree, collect the SIDs, and terminate the processes.

Pgrep implements the algorithm for walking, collecting, and process killing by session ID. Use the following snipped:

pkill -s <SID>

Nohup propagation to process descendants

Ignored signals, like the ones ignored with nohup, are propagated to all descendants of a process. This propagation was the final bottleneck in my bug hunting exercise last week.

In my program — an agent for running bash commands — I verified that I have an established a bash session that has a controlling terminal. It is the session leader of the processes started in that bash session. My process tree looks like this:

agent -+

+- bash (session leader) -+

| - process1

| - process2

I assumed that when I kill the bash session with SIGHUP, it kills the children as well. Integration tests on the agent also verified this.

However, what I missed was that the agent is started with nohup. When you start a subprocess with exec, like we start the bash process in the agent, it inherits the signals states from its parents.

This last one took me by surprise.